While writing my recently-completed fantasy Through the Silver, I thought a lot about the novels and stories I had read as a child, works of mystery and magic that I realized have worked their way well below any conscious observations I might have about them into the dreamsoil of my imagination.

For many of these, I can recall not only the stories and characters but also the act of reading them itself. The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula K. LeGuin is the first book I remember reading from beginning to end without stopping. The afternoon light dimmed into night through the window above my bed, and I carried the paperback spread open across my palm as I fumbled down the hall to the bathroom.

Okay, the novel is not very long, but as a fourth grader, it felt like an exciting achievement to absorb an entire narrative in single arc. I had read and enjoyed the first book in LeGuin’s Earthsea series, so I was prepared to like this one as well, but I had not realized the most of the story would be set in one of my favorite childhood fantasy locales: underground, in a cavern. Most of the interesting stuff happened underground in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, which I had read not too long before—Gollum’s cave, the home of the dwarves, Smaug’s lair, etc.—but the visceral sensation of rooms and passages under the earth is even more central to this book.

The Tombs of Atuan unfolds the story of a young girl who is forced to adopt the role of priestess to the nameless gods haunting an underground chamber and a labyrinth of tunnels beneath the convent-like community of women and eunuchs where she lives. Officially, she is the only person allowed into these caverns although other characters break this rule, including Ged, the title character from the first novel, A Wizard of Earthsea. He is searching for a powerful artifact, and when the girl discovers him, she imprisons him for a time before events lead them to help each other to escape from their differing forms of imprisonment.

What struck me most about the novel were the ideas of darkness and secrecy, tunnels full of ancient spirits and treasure that had never seen light, and the need for the girl to learn how to negotiate the hazards with senses other than sight. I also loved that there were maps in the front of the book: of the buildings on the surface, and of the tunnels and chambers below.

I had done quite a bit of cave map drawing myself. These were poorly drafted sketches of pairs of squiggling lines in black pen on sheets of typing paper that probably looked to the uninitiated like obsessive diagrams of bowls of spaghetti or a very upsetting gastrointestinal tract. The names of important features would be carefully printed nearby, perhaps with a helpful arrow: amazing natural wonders like skyscraper stalagmites, waterfalls, bottomless pits; manmade features like secret hideouts and hidden rooms; and mysteries—tunnels that ended with two parallel broken lines and a final question mark [?]. Even the mapmaker could not claim to know all the cave’s secrets.

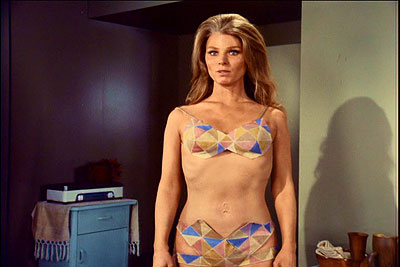

I had a particular fascination with Carlsbad Caverns. I had pored over the issue of National Geographic that featured color photos of most of the highlights, and I had favorite movies that were filmed there, or purported to be set there. For some reason, these movies always seemed to be on the late show, and I would stay up way way past my usual bedtime in the summer to watch them. The 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth with James Mason and Pat Boone. And Gene Rodenberry’s follow-up to Star Trek, a pilot for series called Genesis II, in which a man wakes from decades of suspended animation to find that his lab within Carlsbad Caverns had been cut off by an earthquake and forgotten while civilization collapsed in a nuclear holocaust. He returns to find good-guy scientists trying to rebuild the world while tyrannical mutants stand in their way. I didn’t remember this tidbit, but a summary I found online explains that the mutants are identifiable by their double navels, modelled below by Mariette Hartley.

Genesis II (1973)

Genesis II - Mariette Hartley sporting a double navel

I watched these shows until early in the morning, as if the night were a cave that they and I and the big console television in my parents’ house had all burrowed into.

Around the same time that I read The Tombs of Atuan, my family went down to Carlsbad Caverns in person on a long camper trip that began just south of Salt Lake City and ended a little less than 900 miles later at the southern state line of New Mexico. I loved it all: the flight of the bats at dusk, the chambers as large as cathedrals with formations of intricate pleats and folds, the chill air, the mineral scent. But I was most intrigued by the lunchroom, 1950s Space-Age Modern and 750 feet below the surface.

Carlsbad Caverns Lunchroom

Looking at a vintage photograph of the cafeteria at its height, the folks gathering their box lunches seem a lot like sinners being assigned to the Eisenhower Wing of Dante’s Inferno. There is something about the fact that this dining is taking place in subterranean splendor that gives it an imaginative charge.

Carlsbad Caverns - Box Lunch Lines

Freudians or Jungians or readers of James Hillman’s The Dream and the Underworld have likely already made a proper psychoanalytic assessment of my childhood cave enthusiasms. A hero’s journey into the archetypal and the unconscious. Symbols of sexuality and exploration (all the cavern-centered books and movies I can think of have a weird libidinous pulse to them. In the 1959 Verne movie, Pat Boone strips to a pair of cutoffs then has a naked musical interlude in a natural underground shower, and the leading lady, Arlene Dahl, loses her inhibitions and smiles, smiles, smiles as she whooshes up through the vent of a volcano!)

All I knew was that there was something down there, something hidden, in the dark and the damp, at the end of a maze or behind a bolted door, and I wanted to find out what it was.